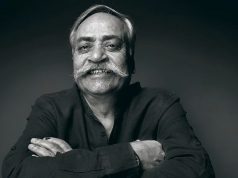

By Ganesh Saili

By Ganesh Saili

There is no mistaking the husky voice at the other end of the phone. It is Moni Ghai, the ex-owner of the twin Kwality restaurants in Mussoorie and Dehradun. In our youth, that’s where you would have found us hanging out. On reading a piece of mine, he remembered a meeting, albeit brief, with Sir David Lean, who happened to be staying with his friend, the Doon School headmaster, the legendary ‘JAK’ or John Martyn.

‘The filmmaker told us about a film called The Bridge on the River Kwai that he had shot !’ he recalls.

The first steam engine was introduced to Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) by the British. The smoke-belching dragon appeared, looming larger than it actually was, a black monster that hissed like a collective of cobras; the locals called it the Iron Demon. The Burghers who drove the ‘monster’ were like our Anglo-Indians in India – an ethnic Eurasian group (limited to Sri Lanka), and they made up the bulk of railway employees there.

The British Commander in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Colonel Nicholson (played by Sir Alec Guinness), perfectly depicts Britain’s reduced role in world affairs. Here was a man using the military discipline of hundreds of years to survive the torture and humiliation, both physical and mental, of being a Japanese Prisoner-of-War, but his addiction to the same discipline and tradition has driven him mad. It serves to illustrate the state of Britain as she clung to antiquated ways in a foolish attempt to save her identity. Together, the POWs could teach their captors, the Japanese, a thing or two about bridge building. This becomes a single-minded obsession for Nicholson. How can one ever forget the POWs marching into a prisoner-of-war camp while whistling Colonel Bogey’s March!

What Sir David Lean forgot to tell the Doon School boys was about the actors who, during the filming, fought like cats and dogs. Recreating the Death Railway was a major expense, as some two thousand yards of a new railway line had to be laid before the bridge was thrown across the Mahaweli River.

‘Action!’ yelled Lean, and the train chugged around a bend and tumbled into the river exactly as planned. Sadly, they found that one of the six widescreen cameras concealed in the location had failed. Understandably, David Lean was hopping mad; he stomped his foot, went into a sulk, and refused to step out of his tent.

Pic courtesy: Manvendra Pratap Singh.

On hearing of the disaster, his friend, Sam Spiegel, flew down to Sri Lanka. The bridge was rebuilt, and for the second time, the train rolled, and the bridge was blown up, hurtling to their doom the hundred rubber dummies dressed as Japanese soldiers, every detail in place – from helmets to buttons and insignia, into the river.

This time around, the British Army Sappers, those famous dam busters, had been hired. It was said that they could blow the icing off a cake and leave the candles in place. They added a special touch by stuffing the last coach with dynamite – when it hit the river, it exploded, and on film, the resultant explosion looked like Japanese exploding munitions.

Years later, I met the actor Victor Banerjee, who had played the hero in A Passage to India. That was the maestro David Lean’s last film.

Sitting under a canopy of a hazelnut tree, in Parsonage, Victor’s lovely home in the hills, he recalls, ‘His eye for detail was something to write home about! I will always remember that while shooting the film, he walked into the beautiful Bangalore Club. adorned with plastic flowers blossoming all over.

‘He looked at the set, wasn’t satisfied, and told the gofers, ‘Add some more coffee to that pool!’ Those were the muddy waters in which Sir Alec Guinness, acting as Godbole, was seen dipping his feet in the film. And before you knew it, pack-up was announced. Not a frame was shot that day!’

Meanwhile, the voice on the phone tells me, ‘We were too young to be impressed.’ No longer so young, Moni Ghai has wound up his affairs and now lives in retirement in Rajpur.

Ganesh Saili, born and home-grown in the hills, belongs to those select few whose words are illustrated by their pictures. Author of two dozen books, some translated into twenty languages, his work has garnered worldwide renown.