Book Review

By Dr Sanjeev Chopra

By Dr Sanjeev Chopra

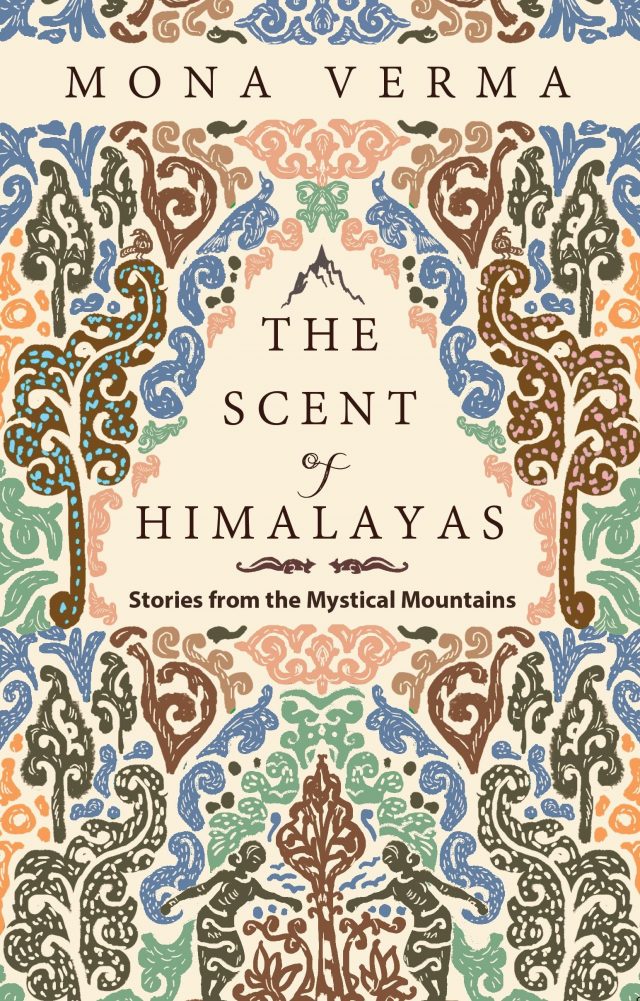

The repertoire of the twenty stories in Mona Verma’s ‘ The Scent of Himalayas – Stories from the Mystical Mountains’ is drawn from Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, the Garhwal and Kumaon regions of Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Meghalaya and the highlands of Assam. They connect us to creation myths, help us understand the prevalent belief systems, resurrect our faith in essential triumph of good over evil, acknowledge the strength of the brave women of the hills, the interconnectedness of humans and nature and the realisation that the symphony of life will have its highs and lows.

Ecological underpinnings

Many stories in this selection have deep ecological underpinnings. Let’s start with Kaafal – the story about the revitalising berry fruit of Kumaon. In this narration, two birds tell the story of a daughter protesting her innocence on being accused by the mother of having eaten the Kaafal, while the berries had actually shrunk on account of the extreme heat. In the Indian astrological tradition, Ashoka’s etymology stems from A- Shoka (the one that alleviates grief) and the Ashoka Vatika (grove) holds a special place for Hindus as this was the refuge of Sita in Raavan’s Lanka. Now, a fruit for mortals, it yearns to return to the land of Lord Indra.

‘Curse of Thirst’ is about the sparrow’s eternal quest for water to quench its thirst. We learn from the story that water bodies – rivers, lakes and oceans – should always be held in reverence, as indeed the ‘Nadi Stuti Sukta’ of Rig Veda tells us. Bhemata is a powerful story which teaches us that Mother Earth is deeply anguished when unripe saplings and fruits are plucked – for they have a life just as we. The Himalayan barbets and songbirds still lay their eggs on the forest floor, hiding them from plain sight with abundant foliage. This is linked to the story of Bhinkanu, the bird which laid her eggs, not in a nest perched on a tree, but on the forest floor – and her quest for justice and redemption from the gods has ensured ample rainfall in the highlands of Uttarakhand.

The Veer Naaris (brave women) of Himalayas

The ballad of Nar Singh and Dhana is now an important Jaagar (folk song) from the land of Askot (eighty forts) which celebrates the valour and love of the brave Dhana who avenges the death of her husband Narsingh. Then we have the historical narrative of Naak Kati Rani, the wife of the legendary King Mahipat of Garhwal. She spared the lives of the retreating Mughal soldiers (Shah Jahan) only on the condition that they cut their noses before fleeing!

Rajula Malushahi celebrates the wisdom, tact and conviction of the extraordinarily beautiful Rajula, a commoner. Despite her father’s fear of annoying the Hun king, Vikhipal, who controlled the trade route of Tibet, which controlled the livelihood of her clan, she is steadfast in her resolve to save her husband Malushahi, the prince of the Katyuri dynasty from the clutches of the former.

From the land of Lepchas

We have two stories from Sikkim. The love story of Rongyu and Rangeet – the rivers which originate from Mayel Lyang, the original name of Sikkim in Lepcha language – and meet at Teesta – is so popular in Kalimpong, Sikkim and Darjeeling that all newlyweds from this region take their blessings from the point of confluence. The second story from Sikkim is about a female Yeti – the mythical, monstrous, ferocious and apelike Jyamphi Moong. She is fascinated by the melodic Puntaong Palit (flute) of Atek, a young Lepcha rancher who played it with such perfection that she wants to learn it. But he is terrified of her and is succesful in getting out of her clutches – but I must keep the ending a secret – for a review cannot reveal every ending!

Stories connected with the Mahabharata

The Maha Mrityunjaya Jaap (victory over death), also called the Triyambakam mantra, is recited by millions of Hindus every day to invoke the blessings of Lord Shiva, is linked to the Yamakeshwar temple on the banks of the Nayar River in Pauri Garhwal to celebrate Rishi Markendya’s defiance of Yama – the god of death. It is believed that Pandavas visited this temple in the period of their exile. The story of Panch Kedars is also drawn from Mahaprashthanika – the seventeeth Parva of the Mahabharata. The hump in Kedarnath is that of Nandi – Shiva’s incarnation -trying to escape his capture from Bhima. Legend has it that Shiva was quite cross with the Pandavas for killing their kinsmen (gotra hatya) as well as Brahmans (Brahman hatya) in the Mahabharat war. The arms appeared in Tung Nath, the nabhi (navel) and stomach surfaced in Madhyamaheshwar, the face in Rudranath, and the head and hair at Kalpeshwar. We also learn about Vyas Pothi and Ganesh Gufa – the abode of Ved Vyasa and Lord Ganesa, where the Mahabharata was written as Jai Gatha.

The last story, Kaala Paaja, is from Kullu-Manali in the Pir Panjal range of Himachal. This is about Guru Kapish, and his young acolyte Kirnu, who set out in the search of Kaala Paaja – the black twig with age reversal properties – for while the Guru is getting younger, the disciple is now a frail old man!

Bedtime Stories

Mathi Baithan Chor (The thief on the mezzanine) is a delightful bedtime story for children. When a grandmother cries out that the one on the top knows the truth – she is referring to Lord Almighty- but the thieves on the ground floor and basement think that their own partners-in crime on the top floor have given them away, and thus all of them are caught and given a good thrashing by the villagers!

Navid and Yachh takes us to the glens of Kashmir, where Navid the barber gets too greedy after receiving the boon from Yachh (Yaksha), a spirit in the body of a civet cat. The moral of the story is loud and clear: live within your means and avoid unnecessary pomp and glamour.

The Khasis – a matrilineal group from Meghalaya – trace the origin of humankind on earth to Lumsohpetbneng – the revered spot from where the golden ladder connects heaven and earth. Because the seven clans who were asked to live on Earth forgot their covenant with the Almighty, the connection was in danger of being lost forever. However, as the rooster agreed to sacrifice his life to save humanity, the gods have blessed it to be the first to receive the light of dawn.

Another fine bedtime story from Kumaon is about the tradition of offering flour, milk and jaggery laddoos to Kali (the intelligent crow) to ward off the evil eye and protect their children, especially on the occasion of Makar Sankranti (14th January).

Tejimola from Assam is a Cinderella type story, but with a twist. After being killed by her cruel stepmother, Tejimola takes rebirth as a jackfruit, bitter gourd and betel vine before being resurrected in her human form. But in another version of the story, when her father presses her to get married, she prefers to merge back with nature.

Last, but not the least, a story with a social message

‘Vani Vilas’ recalls the contribution of the great Sanskrit scholar, and his sons Lakshmi Vilas and Partha Sarthi Dabral, in busting the caste based and sectarian biases prevalent in the hills of Pauri Garhwal where the dominant upper caste families treated the shilpakars (carpenters, blacksmiths, coppersmiths, barbers and all other artisans) with absolute contempt.

Sanjeev Chopra is the curator of the Valley of Words : a pan India Literature and Arts festival based out of Dehradun. He is currently a Senior Fellow of Contemporary History at the Prime Ministers Memorial and Library and a Trustee of the Lal Bahadur Shastri Memorial . He is also on the Academic Council of the National Centre for Good Governance and the National Institute of Disaster Management . His recent books include The Great Conciliator: Lal Bahadur Shastri and the Transformation of India, and We the People of the States of Bharat : the making and remaking of India’s internal boundaries .