By Pradeep Singh

By Pradeep Singh

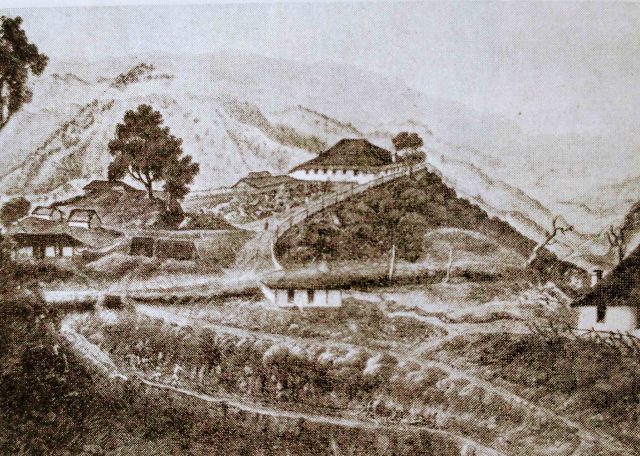

The salubrious climate of the Valley, especially its central and upper parts, was godsend for the British and other Europeans and they flocked here in the decades just after the Anglo-Gorkha War. Finding timber in abundance, the settlers and the government officials built comfortable bungalows, clubs, cantonments, and soon set foot atop the Mussoorie ridge and Landour. The brunt of this first phase of building flurry was faced by the surrounding forests and hillsides where from came deodar and pine sleepers and other building materials. In the Valley, Sal, Teak, Khair and Shisham were the choice for building and furniture. Alarm bells rang but faintly and fell silent in the bureaucratic crevices.

Though the railways came to Doon at the start of the 1900s, yet its forests contributed to this leviathan enterprise. From a modest 35 kilometres in 1853, the railroad covered over 51,000 kilometres by 1910 and, for every kilometre of rail-track, nearly 450 sleepers of Sal and Teak wood were consumed. In neighbouring Garhwal, the exploits of Frederick “Pahari” Wilson in supplying sleepers to the railroads companies practically decimated the hillsides of all valuable timber. The story of denudation of Doon Valley’s forests wasn’t much different, the only saving grace being that these depredations roused the colonial authorities to the rampant loss of forest cover and consequent damage to the reserve of timber, soil erosion and dessication of land surface. The impact was felt at the extremities of the subcontinent. The navigable rivers, the Hooghly and Ganga started silting at their estuaries preventing safe passage for riverine transport vessels.

Though the railways came to Doon at the start of the 1900s, yet its forests contributed to this leviathan enterprise. From a modest 35 kilometres in 1853, the railroad covered over 51,000 kilometres by 1910 and, for every kilometre of rail-track, nearly 450 sleepers of Sal and Teak wood were consumed. In neighbouring Garhwal, the exploits of Frederick “Pahari” Wilson in supplying sleepers to the railroads companies practically decimated the hillsides of all valuable timber. The story of denudation of Doon Valley’s forests wasn’t much different, the only saving grace being that these depredations roused the colonial authorities to the rampant loss of forest cover and consequent damage to the reserve of timber, soil erosion and dessication of land surface. The impact was felt at the extremities of the subcontinent. The navigable rivers, the Hooghly and Ganga started silting at their estuaries preventing safe passage for riverine transport vessels.

Realisation was late in arriving: the river Ganga drained the Himalayas and upper India and carried four times the silt as compared to the Amazon. With aggressive commercial forestry and over-exploitation of the timber reserves, the land became prone to erosion and monsoons, too, added to this process. Flash floods and lack of rainfall were, both, a feature that further eroded the already stressed soil. Even as early as the 1850s, Lord Dalhousie, the Governor General, sought to arrest this destructive and unmindful exploitation and worked towards setting up of a forestry service.

The bottom-line of the East India Company was pound, shillings and pence. Riverine transport was several times cheaper than transporting cargo by railroad. Silted rivers were bad business for sailing vessels and the Board of Directors of the Company were accountants first and foremost and, hence, remedial action plans were drawn up to regenerate the forests across the country and the start would be made from Dehradun.

With the initiative taken by Lord Dalhousie it was soon decided that there should be a dedicated cadre for management of forests and the Imperial Forest Service was on the planning board. However, already by 1856, Dietrich Brandis, a Prussian botanist on the rolls of the government, had introduced scientific forestry in India at the behest of the government. Eight years later, in 1864, the Imperial Forest Service was created with the active participation of Brandis.

The creation of the Forest Service had its own share of teething troubles as the Revenue Department of the government was clear in its general policy that such a new Service would have to be self- supporting and generate its own budgets for its activities. This obviously had implications for the manner in which the Service would orient itself to manage, both, the regeneration of forests, maintain stocks of timber and as well as generate surplus income. Thus, ideals and pragmatism had to find a common ground, and this is what happened in Doon and elsewhere. But our concerns are directed to Doon for the present.

The long association or affinity that the Doon Valley has with formal forest management is due to the setting up of the Forestry School in 1878 under Col. Frederick Bailey with the objective of training Indians to manage the state forest departments. The scope of the school was expanded to include in 1907 a research institute where British foresters were prepared for joining the British Forestry Commission. Interestingly, the professional and academic inputs for training and research into disciplines of Forestry did not come from England where forests were long gone and no local knowledge was available. Some Scottish estates had private forests which had gamekeepers and foresters to manage them. However, the Scotts were skilled to some extent but lacked professional management knowledge. Thus, in the search to find competent people and training facilities, Britain looked to Europe, particularly Germany and France. These two countries had been practicing forestry on more scientific basis but both differed in their philosophy of forest management. Borrowing from both, the British imported into Doon Valley and, later, in the country, a hybrid system combining elements of the German and French models. Yet more adaptations were needed to fit the science of forestry to the sub-continental variations of climate and topography and also, to a degree, the social conditions prevalent at the time.

The bottom-line being commercial viability, the Forest Department looked at only commercially valuable timber and neglected the other trees that grew in mixed jungle environment.

With economics prevailing over ecology, the forest cover of the Doon Valley started taking a new look. Plantations of commercially valuable trees started to edge out the trees not deemed valuable even though they supported a rich biodiversity. Sal trees of vintage rapidly disappeared and regeneration and plantations were not adequate to fill up the gap or make up the deficit. On the other hand, forests became the monopoly of the government, restricting the local village dwellers from availing their traditional needs of forest product like fuel, fodder, foraging, pasture and timber. Wild game, too, was a preserve of the Burra Sahibs and the elite. Social and cultural anchors of much of rural Doon had become a page in history.

The nationalist historians were yet to critique the evils of colonialism when Will Durant, an American philosopher and historian, wrote feelingly in 1930: The British conquest of India was the invasion and destruction of a high civilization by a trading company… utterly without scruple or principle, careless of art and greedy of gain, over-running with fire and sword a country temporarily disordered and helpless, bribing and murdering, annexing and stealing, and beginning that career of illegal and ‘legal’ plunder which had now gone on ruthlessly for one hundred and seventy years.” In all this chicanery of imperialism lay the forest follies of the Doon Valley. (Concluded)

Pradeep Singh is an historian and the author of: Sals of the Valley: A Memorial to Dehra Dun.