By: Ganesh Saili

By: Ganesh Saili

‘With due respect….’ There was a pause. Then followed the question, and instinctively, I knew a curve ball was coming my way as he added: ‘Sir, why are you always writing with nostalgia about the history of Landour and Mussoorie? Have you ever discovered anything new? Or are you just another one chained to the past?’

That question begs an answer.

Yes! Over the years, I have found treasures lying deep, trapped in the murky waters of time. I saw Jack Gibson’s Wilson coins, and discovered that Gen. Dyer’s widow once owned Vincent Hill; that the Jharipani bat was the world’s tiniest bat; and that Maharaja Daleep Singh, son of the Lion of the Punjab Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Lahore Durbar, spent two summers in Castle Hill Estate. My friend Rahul Kohli actually sent me a picture of a watercolour painted there. And now, I’ve helped discover a Sticke Court lost in these hills.

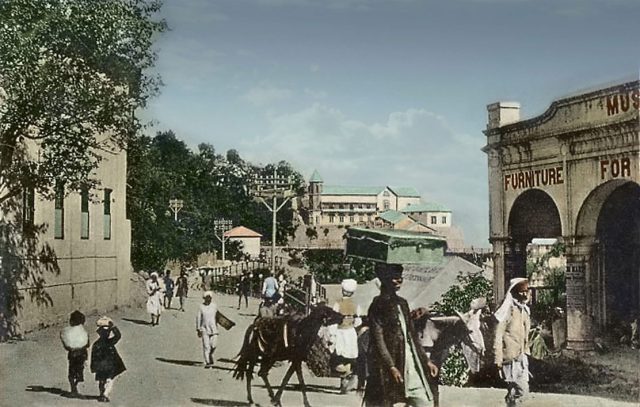

Pic courtesy: Author’s Collectionpeg

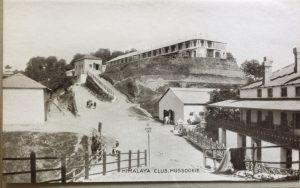

All we had to go on was a single line in Frederick Bodycott’s Guide to Mussoorie (pub. 1907): ‘A Sticke Court was added to the Himalaya Club in 1906, which was placed at the disposal of the members free of charge.’ We (Ruskin Bond and I) dutifully repeated this fact in Days of Wine & Roses (pub 1992). After that, we forgot about it!

Now, three decades down the road, came David Lloyd, an investment banker in the UK, who had brought out a limited edition of Nigel Brassard’s book for me (No. 90 out of the 200 printed), The Rise and Fall of Sticke Tennis.

‘Ganesh! There are just two sticke (pronounced ‘stickay’) courts in India: one in Shimla and the other in Mussoorie,’ gushed David. Now, truth be told, I had never known such a game existed.

We went, the two of us, to the old Himalaya Club (now renamed the Himalaya Castle Hotel) to walk in on Smita Vaish, the owner’s pretty daughter, but she was off on her errands.

Worse still, she hadn’t heard of it either.

‘There’s a large hall upstairs, where we play badminton!’ she says with a smile, gets into her car and is gone.

Climbing a flight of stairs, as old rusty locks are opened and the doors flung open, we stand, gaping in silence, for this unveils a slice of our history. This was where, in the once-upon-a-time days, the soft ball bounced on the court, when ladies wore long skirts while playing, and no smashing was allowed.

A hundred years later, Nigel’s precious book fills in the rest: ‘It was a simple and highly sociable game played by people of different abilities.’ A covered game court simply meant it could be played in any weather.

Sticke tennis and lawn tennis were both discovered in the 1870s, though fifty years later, the two games took two entirely different paths. In a cold place like Mussoorie, with limited choices for folks who stayed back, life during the winter could get dull and lonely. The choice was either to hibernate like a bear or play tennis in shirt sleeves after sunset in luxurious warmth under a covered roof. Some preferred the latter.

Two months after his arrival on 2nd December 1884, Lord Dufferin, the Viceroy in Bombay, ‘was happy this afternoon in opening his own particular tennis court. Several gentlemen in scarlet uniforms attend to pick up the balls, but they are to be exchanged for small boys, lightly clad.’ Dufferin had no problem with their attire, but ‘a higher authority has commanded that they must be draped.’

In far-off Shimla, by April 1887, the Viceregal Lodge (now the Indian Institute for Advanced Studies) had a sticke court. We learn that it was ‘a great boon to all the young men there.’

David tells me about a new entrant in the Delhi office who, on hearing of a ‘Rocket Court’ in South India, quietly sought a transfer halfway across India. He had hoped to discover the place where the Tipu Sultan – the Tiger of Mysore – might have tested his artillery shells.

‘Guess what he found?’ asks David, and answers his own question: ‘No rocket! Just a racquet court!’

Ganesh Saili, an author-photographer, has written and illustrated twenty books, some of which have been translated into over two dozen languages. He belongs to those select few who illustrate their writing. His work has found publication in periodicals, columns, and journals.