By Dr. Satish C. Aikant

By Dr. Satish C. Aikant

Nehru is often accused of being overtly Anglicised and partial to the word India but the fact of the matter is that he was not averse to using the word Bharat. In a passage in The Discover of India Nehru writes: ‘Sometimes as I reached a gathering, a great roar of welcome would greet me Bharat Mata ki Jai – Victory to Mother India! I would ask them unexpectedly what they meant by that cry, who was this Bharat Mata, Mother India, whose victory they wanted? And so question and answer went on, till they would ask me impatiently to tell them about it. I would endeavour to do so and explain that India was all this that they had thought, but it was much more. The mountains and the rivers of India, and the forest and the broad fields, which gave us food, were all dear to us, but what counted ultimately were the people of India, people like them and me, who were spread out all over this vast land. Bharat Mata, Mother India, was essentially these millions of people, and victory to her meant victory to these people. You are parts of Bharat Mata, I told them, you are in a manner yourself Bharat Mata, and as this idea slowly soaked into their brains, their eyes would light up as if they had made a great discovery.’

When Nehru’s book was published, three names, Hindustan, Bharat (or Bharatavarsha) and India, coexisted in the subcontinent. Of constant usage also was Hind, as in ‘Jai Hind’ (Victory to Hind), that Nehru, like several other political leaders, liked to proclaim as a rousing celebration at the end of his speeches. At the time of independence, the names Bharat, India, Al-Hind and Hindustan coexisted to designate the Indian subcontinent. Those who, like Nehru, used them side by side understood their differences and knew how to interpret their contrasting usages, even if, given the complicated history of each, they did not agree on the nature of their differences.

Let us briefly examine the origins of these names. Take the name India. Since its ancient use by Greek (Indikê) and Latin (India) authors, it has been applied in a variety of ways. Or take the word Hindustan, which was already used in Persia in the third century BCE to refer to the land lying beyond the Indus River. In 1950, the drafters of the Constitution of the larger of the two successor states of British India decided how the country should be known. In the opening Article of the Constitution of India they wrote: ‘India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States.’ Two names: one, India, associated with the foreigners; the other, Bharat (Sanskrit bharata, also bharatavarṣa), perceived as native because it was found in ancient Sanskrit literature such as the Harivamsa Purana.

In the Puranas and other Sanskrit texts of the first centuries of the Christian era, Bharata refers to the supraregional and subcontinental territory where the Brahmanical system of society prevails. It seems to have absorbed the older and spatially narrower toponym Aryavarta (the land of the Aryas). We also have reasons to believe that the traditional depiction of Bharata was transmitted over many generations down to the colonial period.

In the compound term Hindustan the word ‘Hindu’ itself raised the difficulty of interpretation. From being a geographic and ethnic term, it became a religious term, as in the late nineteenth century slogan ‘Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan’ that linked national identity to one language, one religious denomination and one territory.

The older and native name Bharata became a workable concept for the national cause despite the forcefulness with which the British conception of ‘India’- and all it entailed in terms of spatial and political unity- was propagated and imposed. Hindustan too remained a worthy candidate for the same cause, as, among other reasons, it could claim a political trajectory that was associated with the Moghul Empire and therefore predated the British colonial period. It also underlines the contribution of the Moghuls to the development of an Indian national consciousness. It was during Moghul rule rather than during British rule that political unity had been achieved strengthening the already existing cultural unity of Bharata, allowing its inhabitants to develop a complete sense of belonging together, irrespective of their religions.

In 1904 when he penned his famous patriotic poem in Urdu ‘Hamara desa’ (Our Country), Mohammad Iqbal also associated Hindustan with Indians at large and with a composite religious culture: Sare jahan se accha Hindustan hamara /Ham bulbuleṃ haiṃ us ki, ye gulsitan hamara / Mażhab nahiṃ sikhata apas men bair rakhna/ Hindi hain ham, vatan hai Hindustan hamara emphasising that our country Hindustan is the best in the whole world, and that religion does not teach mutual hatred. We are Hindi, Hindustan is our native country.

The attempt by Savarkar to Hinduize the name Hindustan was another crucial moment in the naming of the emergent nation. Whereas Iqbal called the inhabitants of Hindustan by the old appellation Hindi, which signifies ‘Indian’ in the ethno-geographical sense, Savarkar called them Hindus, and reserved the term only for those Indians who considered Bharat both as their Holy land (puṇyabhumi) and as their fatherland (pitribhumi), by which he meant the Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs but not the Muslims and Christians. In that he produced an exclusive Hindu vision of India. For Savarkar Hindu does not mean a believer of Hinduism, it is a national and cultural designation. Hindus, he declared, are bound by their own culture (saṃskṛti).

The Bharata – a cultural space whose unity was to be found in the social order of dharma – was a pre-national construction and not a national project. At the time of independence, India and Bharata were equally worthy candidates to baptize the newly-born nation, along with ‘Hindustan.’ But the opening article of the Constitution discarded Hindustan and registered the nation under a dual and bilingual identity: ‘India, that is Bharat.’ One name was to be used as the equivalent or the translation of the other as exemplified on the cover of the national passport, where the English ‘Republic of India’ corresponds to the Hindi ‘Bharata gaṇarajya’, or, perhaps even more tellingly, on India postage stamps, where the two words Bharata and India are collocated.

The name Hindustan has continued to be widely used in spite of, or may be thanks to, its plurality of meanings. It is likely that these names will continue to be interpreted as giving new meanings to India’s national identity, which is an ongoing process.

In a way, traditional Hindus still mentally reside in Bharata, as their ancestors did: at the beginning of their daily rituals when they express their intention (saṃkalpa) and identify themselves, they not only give their name, caste, lineage, etc., the period of the year, the date, but also their location in space, and this they do by using the word Bharatavarṣe.

My personal view is that India and Bharat can continue to be used interchangeably as the Preamble to our Constitution clearly suggests. However, officially, we could retain just one name Bharat after making suitable amendment in the Preamble. Surely if Gandhi called the newspaper he edited in South Africa Indian Opinion and Subhash Chandra Bose called his military outfit the Indian National Army (or Azad Hind Fauz, not Swatantra Bharat Sena) the word Indian was not being used with a colonial mindset. We should keep on using India or Bharat as the context decides.

Anyone can see through the timing and urgency of the name change to Bharat. It is all politics. But if something good comes out of this politics so much the better. If in the process of decolonisation Ceylon can became Sri Lanka and Burma can become Myanmar there is no reason why our country cannot be singularly called Bharat.

Having named umpteen government schemes after India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has suddenly discovered the virtues of Bharat. If he takes a break from the serial Mann Ki Baat he may even write a book with the title The Discovery of Bharat (or Bharat Ki Khoj) to rival Nehru’s well known book. Nehru, though, is inimitable.

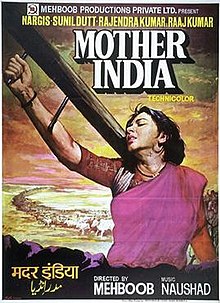

When Katherine Mayo wrote Mother India it was done to denigrate India and Indians. Mehboob Khan’s cinematic opus Mother India with Nargis in her iconic role was a homage to the spirit of the nation. So, it is the intent and the context which determine words that in the final reckoning do matter.

(The writer is former Professor and Head of the Department

of English, H.N.B. Garhwal University)