By: Ganesh Saili

By: Ganesh Saili

We are like that only. Mussoorie-Landour looks like a distended octopus spread-eagled from Haunted House to Cloud End, only nineteen square miles. Even if you add a minuscule cantonment spread over 1040 acres, we are still small and no big deal. If you were to go out looking for someone, you would discover that we locals have named the cottages in honour of the owner.

Ask for ‘Motey-ki-Kothi!’ and you’d be in trouble because it could be any old Fatso’s house. In doubtful cases like this, you have to be more area-specific. Of course, I am aware that it is most impolite! But that’s the way this cookie crumbles. May I suggest you make it easier on yourself by learning to take it with a pinch of salt?

‘Kutta-khana’ or the Doghouse is the old name of Kirkland Estate, famed in its times for the owner’s racing hounds; Redburn, which is now a rabbit warren of guest houses, was ‘Lal muuhwaley ka ghar’ or ‘home of the red-faced one.’ Do not expect traces of a menagerie near the bus stand just because the place is called Chidyawali Kothi. Whilst Masani Lodge refers to the old Masonic Lodge near Picture Palace. Chiselled or laser-burnt into our collective memory, these names refuse to disappear.

People were shapes, rather than names. There used to be this bent-double fellow who worked as a meter reader alongside my father in the electricity office. While mentioning him, folks would hunch their backs like a camel.

‘Mukand Ram,’ said he to my father one day. ‘Go to Kingcraig and bring my wife home!’

‘How will I know who she is? I’ll look like an idiot asking every other girl if she is your wife?’ Father tried valiantly to wriggle out of it but it was futile – the chap refused to take no for an answer.

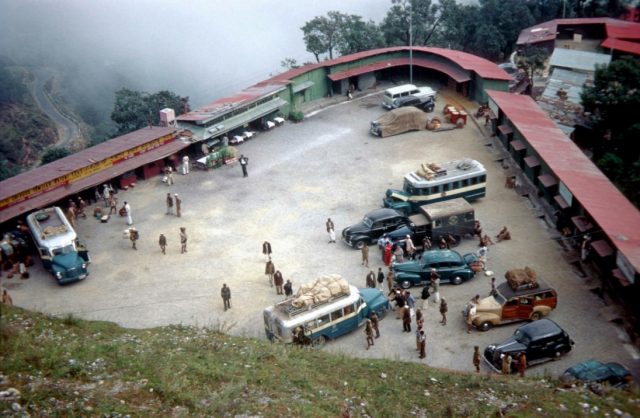

Pic: Author’s Collection.

‘Look around for her. She’ll have no male companions.’ Well, that was as clear as mud! Anyway, my father went to the bus stand, found her, and brought home the bashful bride, and they lived happily ever after. He had arrived in India from Faridkot in Pakistan in 1947 during the Partition. He was a gifted storyteller – to this day I remember that after one of my rough days at school, he comforted me with: ‘When I was in school, one of my teachers took a dislike to me. He got pleasure in walloping me on the knuckles with a ruler!’

He chuckled at the memory: ‘One day I plunged my hands into the cold waters of a spring-fed canal flowing through our school; my hands swelled up, and when I got home, my father took one look at them and stormed off to the school and raised Cain.

‘That!’ he said with finality, ‘was the last time the old codger dared to walk down my row at school!’

Walking past his table one day, I noticed him scribbling, almost furtively, in a diary. ‘What are you writing?’ I asked.

Puffing his chest proudly like a pouter pigeon, he said, ‘Kinarey-Kinarey – doesn’t it sound good for a film title?’ he asked me. In that dark, musty office, he had written a screenplay for a film to be shot by his cousin in Bombay.

As luck would have it, news came that the film producer had passed away very suddenly.

His picture – made in the heydays of the film publicity department in Bombay – hangs over the mantelpiece of their sitting room today. Of course, the garland of dusty wood shavings has seen better days. The trouble is that even the late lamented doesn’t know what he’s doing hanging on this wall.

It’s the same dazed look that Tungal, the road inspector, had – if you were to ignore his moustaches fixed perpetually at ten minutes to two.

‘Bibi ji!’ he would say to my mother. ‘Give me a touch of ghee please.’

‘What will you do with it?’ asked my mother, innocently.

‘Can’t afford the stuff! Too expensive! Rubbing it on my moustaches makes them shine. Plus, the bonus is that I walk around getting a whiff of the real stuff all day.’

Ganesh Saili, author-photographer, has written and illustrated twenty books, some translated worldwide into more than two dozen languages. He belongs to those select few who illustrate their writing.